Scientists get dirt on mystery plant

May 5, 2009, by Kim mcguire, www.stltoday.com

The quest to solve a 70-year-old mystery led Rainer Bussmann and Douglas Sharon to northern Peru to interview traditional healers, or curanderos, about a plant that seemingly vanished more than a thousand years ago.

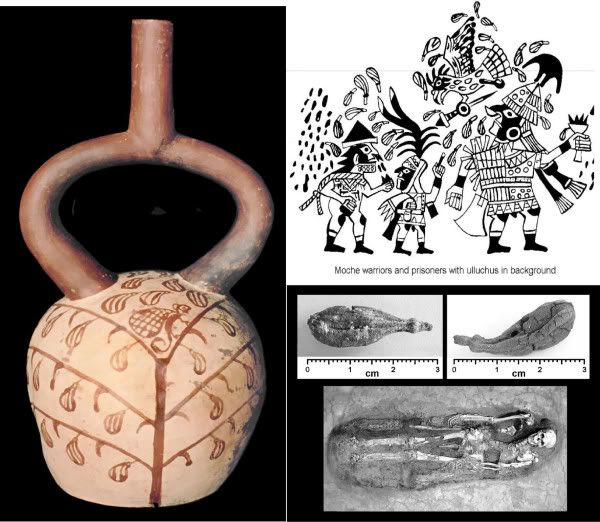

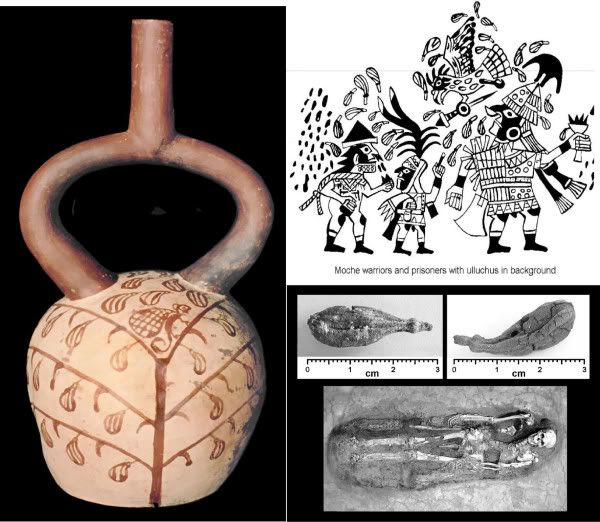

Known as the Ulluchu, the plant turns up in ancient artwork, often seen floating over the soldiers marching off to be sacrificed or flying priests.

But while the curanderos have heard of the Ulluchu, it is not something they use. They cannot describe the plant, and it has no place in their language.

Almost eight years later, however, Bussmann and Sharon have identified the Ulluchu while showing how the plant might have played a key role in human sacrifice. Not only does it appear the plant triggered hallucinations for priests, but it also helped get the blood flowing for those on the sacrificial altar.

And in a surprising twist, the discovery may have turned up modern medical therapies for some age-old health problems.

"For the last 70 years people have been trying to identify this fruit but couldn't," said Bussmann, an ethnobotanist at the Missouri Botanical Garden. "And when our work started, I thought to myself, 'This is not going to be simple.'"

To understand how Bussmann cracked the case of the Ulluchu, the story goes back to 1930. That's when a Peruvian archaeologist first noted the appearance of a comma-shaped fruit frequently shown in the artwork of the Moche, a agriculture-based culture that lived in northern Peru from A.D. 100 to 800.

The archaeologist dubbed the fruit Ulluchu, and scientists have been trying to identify it ever since. Cousins of the papaya and wild avocado are just some of theories that have been scientifically dismantled.

Bussmann became intrigued by the Ulluchu mystery while working at the University of Texas. And in 2001, he and Sharon began conducting fieldwork in northern Peru, home of the Moche.

"We would go to these markets and people would say, 'We think we know what that is, but it's not being sold here,'" said Sharon, the retired director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California-Berkley. "Well, one of the reasons it wasn't being used is because the Ulluchu seems to show up during sacrifices. And no one is being sacrificed anymore."

They did find some evidence in the Quechua language, where Ulluchu roughly translates to "penis pepper."

More on that later.

Still, Bussmann had to sort through more than a thousand botanical suspects in one of the most biodiverse spots in the world in hopes of singling out the Ulluchu.

Then a breakthrough.

Archeological excavations at the ancient Moche city of Sipan and the tombs of Dos Cabezas unearthed actual desiccated remains of the fruit. And true to the Quechua translation, the plant indeed has a phallic shape.

"Rainer is a first-rate taxonomist," Sharon said. "He studied every physical characteristic of these plants until he was absolutely certain we had it."

Bussmann began to suspect their elusive plant had hallucinogenic properties. Remember the flying priests? One of them appears to be holding an instrument that Bussmann believes is snuff tube.

With it, priests might inhale ground Ulluchu seeds, get high, and then commence with the sacrifices, he deduced.

"So imagine you're a priest and it's your job to convince God to stop the rain," Bussmann said. "You need some pretty strong stuff."

Bussmann began closing in on a genus of fairly common plants known as Guarea that are found throughout Peru's lowland forests.

He determined that the plants contain compounds that could cause hallucinations if the seeds were ingested. Another effect of eating those seeds would be elevated blood pressure.

Getting the blood to flow quickly would certainly aid in sacrifices, Bussmann thought. And it would explain why the soldiers about to be sacrificed appeared to have erections in the scenes that Moche drew.

What might explain that physical reaction to pending death?

"That was what really got the bell ringing for me," Bussmann said.

When Bussmann compared specimens of Guarea kept in the garden's herbarium to drawings of the Ulluchu that were unearthed about a decade ago, he knew he had a match.

"When I saw the Guarea, I thought, 'That's pretty conspicuous looking.'"

In late March, Bussmann and Sharon published their findings in a scientific journal, identifying Guarea as the mystery plant, Ulluchu. So far, no one seems to be challenging the identification.

Bussmann, director of the garden's William L. Brown Center for Plant Genetic Resources, plans to further study the plant's chemistry and suspects it might have applications as a blood pressure and erectile dysfunction treatment.

Meanwhile, archaeologists continue to dig at Moche burial sites. Because of Bussmann and Sharon's discovery, they know a little more about human sacrifices, many of which occurred during times of extreme weather events and were meant to pacify the gods.

"When life gets unsettled, people find ways to cope with it," Bussmann said. "It all makes perfect sense now."

May 5, 2009, by Kim mcguire, www.stltoday.com

The quest to solve a 70-year-old mystery led Rainer Bussmann and Douglas Sharon to northern Peru to interview traditional healers, or curanderos, about a plant that seemingly vanished more than a thousand years ago.

Known as the Ulluchu, the plant turns up in ancient artwork, often seen floating over the soldiers marching off to be sacrificed or flying priests.

But while the curanderos have heard of the Ulluchu, it is not something they use. They cannot describe the plant, and it has no place in their language.

Almost eight years later, however, Bussmann and Sharon have identified the Ulluchu while showing how the plant might have played a key role in human sacrifice. Not only does it appear the plant triggered hallucinations for priests, but it also helped get the blood flowing for those on the sacrificial altar.

And in a surprising twist, the discovery may have turned up modern medical therapies for some age-old health problems.

"For the last 70 years people have been trying to identify this fruit but couldn't," said Bussmann, an ethnobotanist at the Missouri Botanical Garden. "And when our work started, I thought to myself, 'This is not going to be simple.'"

To understand how Bussmann cracked the case of the Ulluchu, the story goes back to 1930. That's when a Peruvian archaeologist first noted the appearance of a comma-shaped fruit frequently shown in the artwork of the Moche, a agriculture-based culture that lived in northern Peru from A.D. 100 to 800.

The archaeologist dubbed the fruit Ulluchu, and scientists have been trying to identify it ever since. Cousins of the papaya and wild avocado are just some of theories that have been scientifically dismantled.

Bussmann became intrigued by the Ulluchu mystery while working at the University of Texas. And in 2001, he and Sharon began conducting fieldwork in northern Peru, home of the Moche.

"We would go to these markets and people would say, 'We think we know what that is, but it's not being sold here,'" said Sharon, the retired director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California-Berkley. "Well, one of the reasons it wasn't being used is because the Ulluchu seems to show up during sacrifices. And no one is being sacrificed anymore."

They did find some evidence in the Quechua language, where Ulluchu roughly translates to "penis pepper."

More on that later.

Still, Bussmann had to sort through more than a thousand botanical suspects in one of the most biodiverse spots in the world in hopes of singling out the Ulluchu.

Then a breakthrough.

Archeological excavations at the ancient Moche city of Sipan and the tombs of Dos Cabezas unearthed actual desiccated remains of the fruit. And true to the Quechua translation, the plant indeed has a phallic shape.

"Rainer is a first-rate taxonomist," Sharon said. "He studied every physical characteristic of these plants until he was absolutely certain we had it."

Bussmann began to suspect their elusive plant had hallucinogenic properties. Remember the flying priests? One of them appears to be holding an instrument that Bussmann believes is snuff tube.

With it, priests might inhale ground Ulluchu seeds, get high, and then commence with the sacrifices, he deduced.

"So imagine you're a priest and it's your job to convince God to stop the rain," Bussmann said. "You need some pretty strong stuff."

Bussmann began closing in on a genus of fairly common plants known as Guarea that are found throughout Peru's lowland forests.

He determined that the plants contain compounds that could cause hallucinations if the seeds were ingested. Another effect of eating those seeds would be elevated blood pressure.

Getting the blood to flow quickly would certainly aid in sacrifices, Bussmann thought. And it would explain why the soldiers about to be sacrificed appeared to have erections in the scenes that Moche drew.

What might explain that physical reaction to pending death?

"That was what really got the bell ringing for me," Bussmann said.

When Bussmann compared specimens of Guarea kept in the garden's herbarium to drawings of the Ulluchu that were unearthed about a decade ago, he knew he had a match.

"When I saw the Guarea, I thought, 'That's pretty conspicuous looking.'"

In late March, Bussmann and Sharon published their findings in a scientific journal, identifying Guarea as the mystery plant, Ulluchu. So far, no one seems to be challenging the identification.

Bussmann, director of the garden's William L. Brown Center for Plant Genetic Resources, plans to further study the plant's chemistry and suspects it might have applications as a blood pressure and erectile dysfunction treatment.

Meanwhile, archaeologists continue to dig at Moche burial sites. Because of Bussmann and Sharon's discovery, they know a little more about human sacrifices, many of which occurred during times of extreme weather events and were meant to pacify the gods.

"When life gets unsettled, people find ways to cope with it," Bussmann said. "It all makes perfect sense now."