Ariocarpus agavoides

A. agavoides' first mention in the context of peyote appears to be in a 1979 Economic Botany article by Bruhn & Bruhn where its chemical study is undertaken due to its relationship to established Ariocarpus species known as peyote, and also for its possible chemical similarities to them. Edward F. Anderson, in his Peyote: The Divine Cactus, mentions A. agavoides "at one time or another (having) been called peyote," but fails to give supporting information of its use other than as a food item. It is a questionable peyote species and does not appear to have ethnobotanical use beyond as a food item and glue due to its internal mucilage.

A. agavoides is known to local inhabitants of Tula, Tamaulipas, Mexico, as "magueyitos" (little agaves) and are collected and eaten for their sweet tasting flesh. I have even heard that a goat herder from the same area eats the plants because, in translation, "they make your head feel good." Their overindulgence is also believed to cause dizziness. The tubercles have even been added to salads at the Top of the Cove restaurant in La Jolla, California, due to their being sweet and bitter at the same time.

This species, along with others in the taxon, are becoming endangered in nature due to the encroachments of man and over collecting. Ariocarpus species were once known as Roseocactus and have been a favorite for hybridization.

N-Methyl-3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine

N,N-Dimethyl-3-methoxytyramine

Hordenine

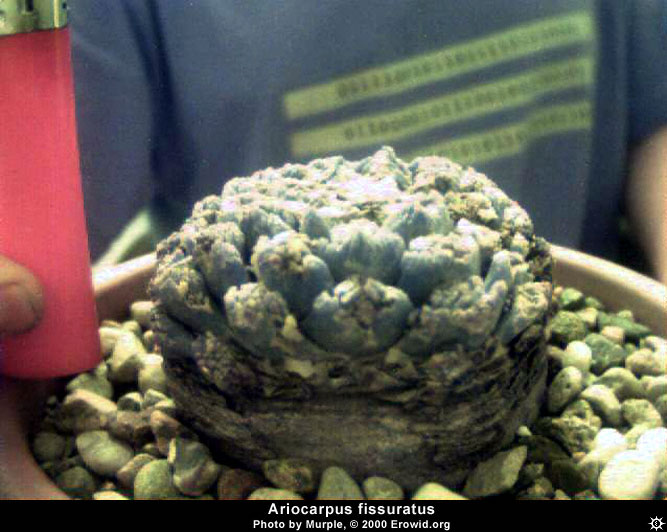

Ariocarpus fissuratus

A. fissuratus is considered one of the most important híkuri of the Tarahumara, being known as "híkuri sunami," a term signifying its ability to "enchain." It is also known as "peyote cimarrón" (wild peyote), a term indicating its unruly nature. This latter designation may be inaccurate as Bennett & Zingg regard peyote cimarrón as being "small, red, and ineffective" and "not used or even touched, since the abuser may die." Carl Lumholtz, in his classic text on the Tarahumara, Unknown Mexico, doesn't even make mention of such a plant as peyote cimarrón, though he does address híkuri sunami. Ivar Thord-Gray, in his Tarahumara dictionary, makes a clear difference between híkuri cimarrón and híkuri sunami, believing the former is "considered the most dangerous peyote, in fact deadly even to the touch, and is therefore never used," while he regards the latter as being "at least as powerful as híkuri wanamé" (L. williamsii). Híkuri cimarrón has been applied toward only one other Cactaceae, Astrophytum myriostigma, while it has been applied to one species of Compositae (Asteraceae) and two species of Orchidaceae.

Though containing no mescaline, A. fissuratus, as híkuri sunami, is, according to Lumholtz, believed by the Tarahumara to be more powerful than híkuri wanamé and be used in the same manner. That this híkuri is considered at least as, or more powerful than, L. williamsii is rather impressive considering the minimal presence of alkaloids, but such a term as "power" should not immediately be assumed to denote that it is more hallucinogenic than L. williamsii. A. fissuratus, like L. williamsii, is highly valued, both medicinally and ceremonially, and its power could lie far from its ability to alter consciousness. One must also consider the possibility that "power" is simply an abridged translation, by a Victorian era westerner, of a report provided by an aboriginal; a report that likely would have been more thorough in its description were it accurately transcribed.

A. fissuratus is frequently used as a medicinal and pain-killing plant, being placed upon wounds, snakebites, and bruises. It is also known to remedy fevers and ease rheumatic pains. Like L. williamsii, it is a medicinal panacea that is used for all orders of disease. Often A. fissuratus is mixed with water and boiled for a few minutes to be made into a strongly intoxicating drink. It is also chewed or drunk as a stimulant for traditional Tarahumara foot-runners, while others will often carry pieces of this híkuri in their belts for good luck. Again, like in prior reference to "power," the term "stimulant" must be considered from the same perspective; that it is not a central nervous stimulant as understood by western culture. It is much more likely that the value of some híkuri as stimulants in running contests is for their ability to focus the mind on the sacred task at hand by dulling pain and suppressing thirst and appetite. Its use in festivals extended past the mid-20th century and is likely used in some form to this day.

The most mythical aspect reported about A. fissuratus is the belief that it has the ability to cause robbers to be "powerless to steal anything where sunami calls soldiers to its aid." Just how it is used to protect ones property had failed to be recorded, but quite possibly it could have been an idol placed in or around the camp or home, or else may have been prayed to for such purpose. Like other important híkuri, A. fissuratus would likely have been venerated as a god with the power of intercession in human affairs.

I am aware of one modern account of the ingestion of A. fissuratus tea. The report indicates non-hallucinogenic effects with strong narcotic pain killing qualities. More complete chemical studies of this genus may prove productive.

A. fissuratus includes a large number of morphological variations. Which of these may be used among the Tarahumara is apparently unknown. A. bravoanus subspecies hintonii (=A. fissuratus variation hintonii) is reported to be used as an exterior salve for general pains and rheumatism after being soaked in alcohol.

A. fissuratus has been successfully crossed with L. williamsii, creating L. williamsii x A. fissuratus hybrids.

A. fissuratus has been called "chaute" or "chautle," terms that are a corruption of "challote," which itself is a Spanish corruption of "peyote."

Hordenine

N-Methyltyramine

N-Methyl-3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine (found in var. fissuratus)

Ariocarpus kotschoubeyanus

According to Helia Bravo in her 1937 book, Las Cactaceae de Mexico, A.kotschoubeyanus is known as "pezuna de venado" (cloved hoof of the deer) or "pata de venado" (deer's foot). The plants titles are interesting not only because of the hoofed shaped tubercles of A. kotschoubeyanus, but also due to the relationship of deer symbolism to L. williamsii, the primary peyote cactus.

A. kotschoubeyanus appears to have mistakenly gained a reputation as a peyote species. This may have occurred through the inclusion of the plant in a listing of peyote species compiled by Richard Evans Schultes, the famed Harvard University ethnobotanist who had studied the use of peyote among the people and tribes of the American southwest and Mexico. In his article, Peyote and Plants Confused With It, Schultes indicated that his information regarding A. kotschoubeyanus was drawn from Bravo's work, but Bravo makes no mention of the plants being known as peyote. Schultes also goes on to state that the species is "said to be either narcotic or medicinal," but he offers no accounts of such usage or where such information may have come from. This of course begs the question of who informed Schultes about this and many other peyote plants' status as "either narcotic or medicinal." It is uncertain if Schultes collected his own data or if he simply extrapolated from prior publications to gain his understanding of narcotic or medicinal cactus. This must be kept in mind regarding all of the other plants that Schultes claimed to be narcotic or medicinal peyote species.

The notion that A. kotschoubeyanus is distinctly known as peyote appears to have been sustained through Anderson's listing of it in Peyote: The Divine Cactus as having "at one time or another been called 'peyote,' or the Spanish diminutive 'peyotillo'."

No solid evidence exist that A. kotschoubeyanus was truly considered a peyote by the aboriginal populations, but no doubt its use in a manner similar to known peyote species, for pains and rheumatism, demands its inclusion in any study of the subject. Like other Ariocarpus species, its mucilage is also known as an effective glue.

A. kotschoubeyanus gets its name from Prince Kotschoubey who paid more than their weight in gold for one of three plants originally brought to Europe in the 19th century.

Hordenine

N-Methyltyramine

Ariocarpus retusus

The Huichol believe that those who transgress the Huichol ethical code or have not ceremonially purified themselves prior to the collection of peyote (L. williamsii) will be led to "tsuwíri" (A. retusus) by supernatural forces and suffer "terrible psychic agonies." They consider tsuwíri a "false peyote" due to its undesirable effects, claiming it is an evil plant that will drive people mad if ingested, and that can also cause permanent insanity. It is considered akin to "kiéri" (Datura meteloides=D. inoxia), a dangerous deliriant Solanaceae species, due to its initial ability to cause seemingly pleasant visual and auditory hallucinations that later mislead the pilgrim away from the group. He will then travel through many terrifying perils, of poisonous creatures, large beasts, and deep pits, leaving him "scratched, full of blood…tired, worn out." He will find himself with "so many cactus spines, so many thorns everywhere," in his clothes, feet, and hands.

Though many peyote are casually cited in the literature as being "false peyote" it appears that A. retusus is the only one to which this title is accurately applied.

A. retusus is used to treat fevers, and most likely has additional medicinal uses similar to other Ariocarpus species and L. williamsii. Sacred Succulents, an ethnobotanical company specializing in "rare, endangered and beneficial xerophytes," claims that recent findings indicate A. retusus' use by "well trained Huichol shamans" who believe it to be a "powerful ally." They also mention how the local population has popularized the smoking of the tubercles. Anderson also supports a more positive role of A. retusus in Huichol culture, stating that it is "used in the harvest festival and other ceremonies also involving peyote." Anderson does not make any bibliographic reference to his source, as he regularly does, and he may have gained his information from uncited personal communications or direct observation.

"Peyote," "chaute/chautle."

Hordenine

N-Methyltyramine

N-Methyl-4-methoxyphenethylamine

N-Methyl-3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine

Ariocarpus trigonus

A. trigonus can likely be considered a peyote cactus due to Bravo's indication that it is known as chaute, a corruption of the word peyote.

In addition to those Ariocarpus species already mentioned, A. scapharostrus has also been informally reported by Anderson to be used medicinally.